On surgery day, my sister-in-law, Patty, and my children, Emily (23) and Solomon (16) walked with me from our house in Little Italy to Toronto Western Hospital. Patty gave my children and me the opportunity to be alone together before they wheeled me to the operating room. The surgery was expected to take 4-1/2 to 5 hours.

Emily’s father, Stephen Parkinson, also a close friend, was with Patty and my children in the waiting room during the surgery.

Emily told me that after five hours had passed, and no one had come out to update them, everyone started getting anxious.

She was pacing the waiting room like a caged zoo animal when, six and a half hours after I was taken to the OR, Michael Fehlings appeared. Emily didn’t recognize him in scrubs, but when he smiled at her and nodded, she burst into tears.

Michael told my kids, Patty and Stephen to get some dinner. I would be in recovery for quite a while.

I distinctly remember waking up in ICU, feeling groggy as I opened my eyes. As consciousness spread over me and I realized where I was, I immediately wiggled my fingers and toes. Success! I survived.

The nurse in charge of me asked me some questions: my name, if I knew where I was. I asked what painkillers they were feeding me, since I’m sensitive to opiates. Fentanyl. On a pump that I controlled. Fucking brilliant. No morphine.

Later that evening, Emily, Solomon and Patty were allowed in. We were all crying with relief. They called Jane and put me on the phone, and I cried with her, too. I was so stoned, I was speaking in my mother tongue, that is, with a Long Island accent.

I was tethered to a network of tubes and wires attached to beeping machines. Some tubes and wires passed through the arms of my gown, its strings untied and untidy, or across my torso. I was covered in blankets with no clear borders.

I wanted the gown off. The good-looking male nurse discouraged this, yet I pushed back, with a heavy accent, “Is it a crime to be naked under the blankets?” The gown came off, discreetly.

My family stayed with me until I surrendered to the fentanyl.

The next morning, my brother, Carl, arrived and with the rest of the family, he followed me as I was transferred from ICU to a private room in the neurosurgery ward.

When my father, Carl Sr., arrived the following morning, I was in rough shape. Clearly stunned, he compensated by making a joke about my hair (or lack thereof). I can only imagine how difficult it was for him to see me in this state.

That day, the food started to arrive.

Under Harriet Eisenkraft’s direction, Emily was informed when to expect a food drop-off, first at the hospital, and when I was discharged a week later, at home. No half-hearted noodle or rice casseroles, but sumptuous, creative and delicious meals.

My friends didn’t just cook for me. They cooked for my children and for my visiting family as well.

My father asked where all the food came from. “My congregation!” I was proud to tell him. Rick and Liora Salter made a huge meal with their own rotisserie chicken. Ellie Goldenberg, Eden Nemari, and Harriet Eisenkraft and Gary Klein brought us wholesome and soul-feeding meals to hospital and home. My rabbi, Aviva Goldberg, and her partner, Dinah Gold, and our chazzan, Daniela Gesundheit, brought a load of yummy organic foods from Carrot Common. Daniela also came with her husband, Dan Goldman (together, they are Snowblink), bearing gifts of food, including handmade, low-GI chocolate.

And there were many others outside the congregation who also contributed following the surgery. Most of my friends are foodies. Krys Verral, for example, would come by on her bicycle with an insulated package containing a number of her luscious vegetarian salads. Margo Kennedy and Karen Turner fed me many times, and surprised me with a gorgeous bouquet of fruit! And so many more people, including my regular dinner hosts, James Summers and Harold Van Johnson, and Steve Roy. (See Dedication)

We didn’t have to cook for a month.

The recovery, nevertheless, was brutal. I ended up reacting to the Fentanyl. Day one after the surgery, any change of position caused blinding headaches, a pain that exponentially exceeded that of natural childbirth, which I have not forgotten.

Morphine and other opiates were not options for me. Even with anti-nausea medicine, I get terribly sick.

When a physician from the Pain Team came into my room on the third evening, she started asking me, “On a scale of one to ten…” and I interrupted her, with tears streaming down my face: “Fucking 13!”

I told her that the pain was worse than childbirth without anesthesia. There had to be something they could do to help me. It’s not acceptable that I’m in so much pain.

On the fourth day after surgery, the problem was identified, first by my brother, then the Team.

The low pressure headaches were caused by a cerebral spinal fluid leak.

It’s hard to sew up the meninges, the covering of the spinal cord, so that it is water-tight. My drain was collecting the pink cerebral spinal fluid so quickly it had to be emptied four times a day. During those few days, with that pain, death would have been a welcome relief.

After the diagnosis, I received a medication that took the edge off the headache so that I could stop wishing I were dead. The following day, my catheter was removed.

Every night, my brother, an infectious disease specialist, stayed late into the night with me, until I fell asleep.

He never told the staff or the medical team that he was a physician, but he watched them, and he asked questions, in the most neutral and inoffensive way possible. It was a highly effective approach, because meds as well as other practices were adjusted as a result.

For several days in the hospital room, my family broke bread together and watched countless episodes of Arrested Development on my father’s iPad, propped up on the meal tray.

Once the catheter was out, a nurse would help me when I needed to use the bathroom. I was dizzy and disoriented and unable to stand on my own. Two days after the catheter was removed, an occupational therapist came in with a walker and helped me to get moving.

Mobilizing was difficult. It was as though these legs under me were not my own. Whose body is this? I wondered.

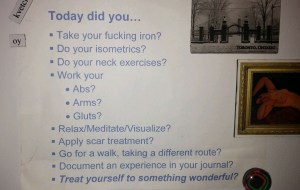

Michael and his team came to see me the following day. I was to walk with the walker for 10-15 minutes, three times a day. A tall order, I thought. But with the help of my family, I overcompensated. I walked 10-15 minutes four or five times a day.

During one round-the-unit tour with my daughter, I had an episode of supraventricular tachycardia—a nuisance more than a health risk. A wave a nausea comes over me and I will actually articulate it (“I need to lie down now”) just before my heartbeat jumps from 60 to 150. The nausea lasts for 15-20 minutes, as my heartbeat gradually drops back down to normal.

Normally I just lie down wherever I am and raise my legs. This time I had to make it back to my room, with a walker, as my heartbeat spiked.

After just a few days, a neurosurgery fellow saw me walking steadily and said, “Look at you! You’re going home tomorrow!” Yahoo!

The horrible drain was removed.

The next morning, Michael Fehlings and his team again came to see me. I was told to drink carbonated beverages, which helps produce cerebral spinal fluid. I was not to lift anything.

Then Michael said, “Let’s go for a walk.” I gingerly got down from the bed and slipped into my robe and Mephisto sandals. I reached for my walker, parked next to the bed.

“No, no walker this time. Take my arm.” And we went for a slow walk around the unit. Michael is tall, a debonair type. It was both odd and fun to walk with my hand on his arm, as though on a date, and trusting him to keep me from falling.

“I know the therapist told you to rent a walker,” he said, “but don’t. Just get a cane. Keep up with the walking, three times a day, always with someone, until you feel comfortable on your own.”

I called the kids with the good news. Released!

A nurse helped me bathe and change into a sexy maxi dress, the one I wore to the hospital on Surgery Day.

My children, Emily and Solomon, arrived at the hospital with a tray of lattes. They packed my belongings. We all thanked the nursing team on the neurosurgery unit, and I gave Michael a big hug goodbye on my way out. This man saved my life. I am so grateful.

We stopped at the two pharmacies on the way home for prescriptions, a cane and a bath chair.

Over the next three weeks, I took up residence on the living room sofa. Still experiencing the low pressure headaches, the pain mitigated somewhat by medication, I felt as though only a part of me had survived the surgery.

I had trouble thinking, probably due to the suite of medications I was on. I was able to bathe and dress myself, but other simple acts of daily functioning were beyond me.

For example, I could not lean forward or bend over. Such movements still caused a blinding headache and tears. But I adapted. I learned to pick up things from the floor with my toes. I could reach a lower shelf in the fridge by doing a deep plié in second position. The ballet lessons of my youth came in handy.

My memory was gone. I could not remember a conversation from earlier in the day. I kept losing my medication, until Emily firmly insisted that the meds never leave the newly-designated “medication drawer” in the kitchen.

I was not allowed to walk on my own, although my house is so small that I can always use my cane and have my other hand on a wall or banister. My children and visiting friends would accompany me on walks outside several times a day. I used my cane and the arm of my companion to balance. Each day, my walks became increasingly longer, reaching 30-45 minutes, three or four times a day.

I had a long and rather dramatic incision down the back of my head, from just below my crown, down the entire length of my neck and ended between my shoulder blades.

The bandages came off a week after returning home, and the skin beneath the incision was raw and red. No longer could I hide my baldness with the beanies. The incision had to be exposed to air at that point, shocking people behind me and frightening small children.

At least I didn’t have to mention cancer when people asked me what had happened. “Spinal cord surgery” was all I said. End of conversation.

Spinal cord surgery sounds, and is, rather dramatic.

Waiting before the procedure, with Emily and Sol.

Now they have to leave. I am still here now.

Is it harder to have to utter that phrase, or harder for the listener to hear?

![IMG_2641[1]](https://elizabethjabraham.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/img_26411.jpg?w=300&h=225)